For whom the barrel tolls

30/12/15 17:24"Oil prices have dropped to $90 a barrel - Crimea is ours! Now it's down to 80 - we'll build a super-bridge to the peninsula! It's down to 70 now - fine, let's make it just an ordinary bridge. $60 - it'll rather be a ferry. 50 - cabin lift, then? What, $40 a barrel? We could always use the shallows... Oh my, $30... Fine, then, Crimea is yours. What the... $20!? Take it! Take it! We'll give you our Krasnodar region as well if you would just take Crimea!"

This anecdote is from earlier this year, and it illustrates how Putin's plans, and those of a number of world leaders, whose countries are highly dependent on the exports of energy resources, have suddenly found themselves in the middle of a flood of excessive oil that no one on the market really needs.

Russia is probably the starkest example, because undoubtedly there's a connection, or rather a contrast, between the emergence of its newly found aggressiveness at the geopolitical stage and the time until just a few years ago, when a barrel of oil was worth well over $100. In 2008, when the Russian-Georgian conflict erupted, a number of people were making a number of forecasts about oil prices soaring up to 150, 200 dollars and beyond. Many seemed to have forgotten that not so long before that, Russia and the rest of the world had somehow coped just fine with prices well below $30.

IHS Materials Price Index data from the last few months shows that the cmmodity (including energy) prices have plummeted by nearly 55% since July 2014, and towards the end of this year they've essentially reverted to mid-2004 levels, i.e. below $37 for the Brent crude. Now a number of new forecasts made by energy institutes and international organisations of renown are claiming that a considerable change until the end of the decade is unlikely. Because we've all learned we can trust these forecasts, right?

The main effect of all this is that we're probably witnessing the beginning of a large-scale redistribution of the oil wealth from the oil producers to the oil consumers. Some are making the argument that this process will turn into an unexpected stimulus for mostly consumer economies like China, Japan, Germany, and Britain.

Out of this group of big consumers, one big absence sticks out: the US, which has always been among the leading oil importers. The US is now registering a record output, and at least formally has canceled its 40-year ban on the exports of US oil. Given the $2 per galon prices (i.e. under the levels of 2009, which was a crisis year), today an average American household spends as much fuel and energy as it did in 2003. Right now, filling the gas tank with milk is actually more expensive ($3.30 per gallon) than with gasoline, WSJ points out.

Of course, not all US producers will survive, and there are lots of oil wells that go out of business because working at these low prices is unprofitable. But still, in September the US registered a 9.4 million barrel per day output, and the forecast is 8.8 million for next year, which is still about 4 million more than the 2011 levels.

As for fracking, despite all the controversy that surrounds it, it has brought back the theories that thanks to the technological innovations, there's practically no limit to economic development. One of the effects of this abundance of easily accessible North American oil and shale gas is that America's interest and role in the Middle East is waning pretty fast, and that's an area that has long defined both America's domestic and international policies.

OPEC, the organisation of the major oil producers is at the brink of turning into a farce. Instead of pursuing its intended cartel policies, it's just registering one quota violation of its members after another, and it can do nothing about the fracking boom in North America - apart from artificially driving the oil prices into the mud and thus potentially shooting itself in the leg in the long run, rendering itself ever more irrelevant by the day, despite the short-term glory of the imminent victory over shale that many are talking about.

Things have reached a point where it's practically everyone fending for themselves. Oil-producing countries with significant currency reserves and relatively low production expenses like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE do have buffers worth hundreds of billions of dollars, which will allow them to survive the battle for market share for a long time, while keeping the production on and on.

It won't be easy for Russia, though. For the last few years, it has increased its social expenses, and has embarked on mega-huge energy projects (mostly benefiting people from the Kremlin circle), plus a number of ambitious geopolitical operations. In the context of the international sanctions, the devalued rouble and the melting currency reserves, Russia is forced to set one oil-production record after another (at least in terms of post-Soviet production), and strive to sell oil at any cost, and postpone the liberalisation of its highly monopolised energy sector indefinitely.

The nightmare scenario of the Russian central bank which was presented for the first time this year, includes oil prices below $35 per barrel, a 2-3% recession, and a 7% inflation. The recent dynamics of the oil prices may've brought that scenario to the fore now more than ever, as the bank's chairlady Elvira Naibulina stated. The Russian ministry of finance is proposing that if the price reaches $40, using their anti-crisis reserves should cease, and the budget expenditures should be cut by 5% instead.

There are some oil-rich countries like Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan in the Russian economic periphery, which were compelled fo devalue their national currencies between 28% and 47% in order to salvage their depleting currency reserves.

For the first time, the word "privatisation" is being mentioned in the context of Rosneft (the proposal is to privatise 20% of the huge state oil company may've hit some roadblocks, granted), and there are suggestions to issue preferential bonds for Transneft. Reuters has hinted that in case of a shortage of loans and investments in the sector, Gazprom has turned to the private Irkutia oil company for a 7 billion cubic meters of gas delivery, in order to meet China's demand. For the last year and a half, Gazprom has signed long-term contracts for exports to the Chinese market worth almost 70 billion cubic meters annually, using two pipelines - but it seems they're short of gas and they can't meet that target - plus, they lack the funds to develop new gas fields.

Times are also difficult for countries like Iraq, Venezuela and Nigeria, and even for the new star on the scene, Angola, where the sharp shrinking of the revenues from the "black gold" is coupled with a rapid devaluation of their national currencies, and a very inefficient management of the economy. So the authorities in those countries are forced to urgently review their budgets and plans.

In Nigeria for example, Africa's largest oil producer, nearly 80% of the budget revenue comes from oil, as well as more than 90% of the exports. In Venezuela, America's third biggest supplier, oil makes up for 96% of the exports, and forms half of the GDP. Venezuelan experts have calculated that every single dollar of dropped prices corresponds to a $700 million loss of revenue for the budget annually.

Iran, now preparing to return to the global market in January with almost 500 thousand barrels daily, won't be enjoying the financial benefits it might have expected, either. Nothing is clear about Libya, a key supplier for Europe, because the civil war is still raging there, and besides, the country's oil-based economy will hardly find alternative sources for recovery.

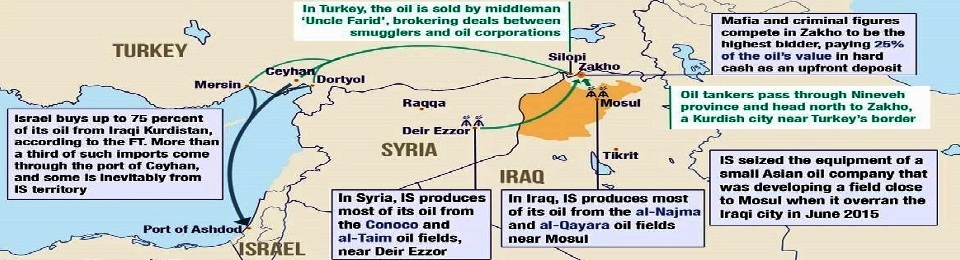

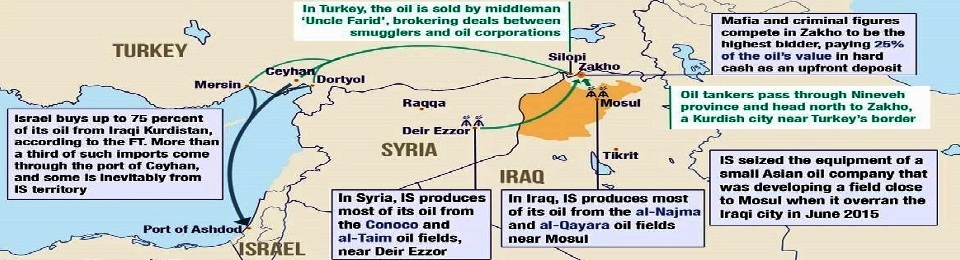

Even the Islamic State had seen its oil-smuggling industry (worth $3 million a day) being put in a delicate situation, long before the coalition started disrupting its oil infrastructure, and long before Daesh had managed to build any stable economic foundations for their ambitious project for a quasi-state caliphate spanning two countries in the Middle East. Now that Russia has started destroying both their oil-producing facilities and their smuggling lines that reach the Turkish border and sink into friendly Turkey, Daesh might be in for quite some trouble.

In Europe, the expected positive effect from every 10% of dropping oil prices would be a 0.1% GDP increase. For this continent, which has been relegated to a second-tier oil producer and energy consumer, private consumption tends to go up, thanks to the cheaper fuels. But because of the strong government presence at the fuel market, and given the relevant excises and other taxes on fuels, the effects of cheaper oil won't be as evident for the end consumer.

In this new situation, the EU which has always been a leading factor in energy innovation and the fight with climate change, will have to find more accessible solutions. Because when oil is so cheap, it's rather difficult to convince the citizens to invest in expensive electric cars, or refurbishing their houses to achieve higher energy efficiency, or pay higher prices for greener energy. Therefore it's logical to expect that quite after the usual European manner, the developers and traders of energy-efficient products would likely ask for subsidies from their governments.

No one would be surprised if the stocks of energy giants like Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron and Exxon Mobil continue to lose their value - in fact, some of them have lost about half of their value in a year. Halting and postponing investments in the sector worth hundreds of billions of dollars has dragged down the companies that supply materials and equipment as well, and also the building companies and steel producers, and the transportation technology companies, etc. It's a chain reaction, including such unpleasant processes like increased financial instability and even a domino-like debt default.

The shareholders and employees in all these industries are hardly that happy with the recent Goldman Sachs and Citigroup forecasts that after Iran (and maybe Libya) return to the global market next year, oil would plunge down to $20 a barrel, at which point commodity markets are very likely to suffer a complete meltdown. They're unlikely to follow the New Year's call to send a thanking card to Saudi king Salman bin Abdulaziz al Saud.

That said, the more industrious among them would probably use the opportunity to find the exact moment when the price of the barrel itself that is used for putting oil in it would exceed that of the oil within it. Then they could start buying lots of barrels of oil, pour the oil out, and start trading with empty barrels. ;)

As for the Peak Oil theorists who used to be very vocal until no so long ago but may've become rather silent lately, I'd tell them not to hasten to despair. They still have a chance of turning out to be right eventually. Or not.

This anecdote is from earlier this year, and it illustrates how Putin's plans, and those of a number of world leaders, whose countries are highly dependent on the exports of energy resources, have suddenly found themselves in the middle of a flood of excessive oil that no one on the market really needs.

Russia is probably the starkest example, because undoubtedly there's a connection, or rather a contrast, between the emergence of its newly found aggressiveness at the geopolitical stage and the time until just a few years ago, when a barrel of oil was worth well over $100. In 2008, when the Russian-Georgian conflict erupted, a number of people were making a number of forecasts about oil prices soaring up to 150, 200 dollars and beyond. Many seemed to have forgotten that not so long before that, Russia and the rest of the world had somehow coped just fine with prices well below $30.

IHS Materials Price Index data from the last few months shows that the cmmodity (including energy) prices have plummeted by nearly 55% since July 2014, and towards the end of this year they've essentially reverted to mid-2004 levels, i.e. below $37 for the Brent crude. Now a number of new forecasts made by energy institutes and international organisations of renown are claiming that a considerable change until the end of the decade is unlikely. Because we've all learned we can trust these forecasts, right?

The main effect of all this is that we're probably witnessing the beginning of a large-scale redistribution of the oil wealth from the oil producers to the oil consumers. Some are making the argument that this process will turn into an unexpected stimulus for mostly consumer economies like China, Japan, Germany, and Britain.

Out of this group of big consumers, one big absence sticks out: the US, which has always been among the leading oil importers. The US is now registering a record output, and at least formally has canceled its 40-year ban on the exports of US oil. Given the $2 per galon prices (i.e. under the levels of 2009, which was a crisis year), today an average American household spends as much fuel and energy as it did in 2003. Right now, filling the gas tank with milk is actually more expensive ($3.30 per gallon) than with gasoline, WSJ points out.

Of course, not all US producers will survive, and there are lots of oil wells that go out of business because working at these low prices is unprofitable. But still, in September the US registered a 9.4 million barrel per day output, and the forecast is 8.8 million for next year, which is still about 4 million more than the 2011 levels.

As for fracking, despite all the controversy that surrounds it, it has brought back the theories that thanks to the technological innovations, there's practically no limit to economic development. One of the effects of this abundance of easily accessible North American oil and shale gas is that America's interest and role in the Middle East is waning pretty fast, and that's an area that has long defined both America's domestic and international policies.

OPEC, the organisation of the major oil producers is at the brink of turning into a farce. Instead of pursuing its intended cartel policies, it's just registering one quota violation of its members after another, and it can do nothing about the fracking boom in North America - apart from artificially driving the oil prices into the mud and thus potentially shooting itself in the leg in the long run, rendering itself ever more irrelevant by the day, despite the short-term glory of the imminent victory over shale that many are talking about.

Things have reached a point where it's practically everyone fending for themselves. Oil-producing countries with significant currency reserves and relatively low production expenses like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE do have buffers worth hundreds of billions of dollars, which will allow them to survive the battle for market share for a long time, while keeping the production on and on.

It won't be easy for Russia, though. For the last few years, it has increased its social expenses, and has embarked on mega-huge energy projects (mostly benefiting people from the Kremlin circle), plus a number of ambitious geopolitical operations. In the context of the international sanctions, the devalued rouble and the melting currency reserves, Russia is forced to set one oil-production record after another (at least in terms of post-Soviet production), and strive to sell oil at any cost, and postpone the liberalisation of its highly monopolised energy sector indefinitely.

The nightmare scenario of the Russian central bank which was presented for the first time this year, includes oil prices below $35 per barrel, a 2-3% recession, and a 7% inflation. The recent dynamics of the oil prices may've brought that scenario to the fore now more than ever, as the bank's chairlady Elvira Naibulina stated. The Russian ministry of finance is proposing that if the price reaches $40, using their anti-crisis reserves should cease, and the budget expenditures should be cut by 5% instead.

There are some oil-rich countries like Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan in the Russian economic periphery, which were compelled fo devalue their national currencies between 28% and 47% in order to salvage their depleting currency reserves.

For the first time, the word "privatisation" is being mentioned in the context of Rosneft (the proposal is to privatise 20% of the huge state oil company may've hit some roadblocks, granted), and there are suggestions to issue preferential bonds for Transneft. Reuters has hinted that in case of a shortage of loans and investments in the sector, Gazprom has turned to the private Irkutia oil company for a 7 billion cubic meters of gas delivery, in order to meet China's demand. For the last year and a half, Gazprom has signed long-term contracts for exports to the Chinese market worth almost 70 billion cubic meters annually, using two pipelines - but it seems they're short of gas and they can't meet that target - plus, they lack the funds to develop new gas fields.

Times are also difficult for countries like Iraq, Venezuela and Nigeria, and even for the new star on the scene, Angola, where the sharp shrinking of the revenues from the "black gold" is coupled with a rapid devaluation of their national currencies, and a very inefficient management of the economy. So the authorities in those countries are forced to urgently review their budgets and plans.

In Nigeria for example, Africa's largest oil producer, nearly 80% of the budget revenue comes from oil, as well as more than 90% of the exports. In Venezuela, America's third biggest supplier, oil makes up for 96% of the exports, and forms half of the GDP. Venezuelan experts have calculated that every single dollar of dropped prices corresponds to a $700 million loss of revenue for the budget annually.

Iran, now preparing to return to the global market in January with almost 500 thousand barrels daily, won't be enjoying the financial benefits it might have expected, either. Nothing is clear about Libya, a key supplier for Europe, because the civil war is still raging there, and besides, the country's oil-based economy will hardly find alternative sources for recovery.

Even the Islamic State had seen its oil-smuggling industry (worth $3 million a day) being put in a delicate situation, long before the coalition started disrupting its oil infrastructure, and long before Daesh had managed to build any stable economic foundations for their ambitious project for a quasi-state caliphate spanning two countries in the Middle East. Now that Russia has started destroying both their oil-producing facilities and their smuggling lines that reach the Turkish border and sink into friendly Turkey, Daesh might be in for quite some trouble.

In Europe, the expected positive effect from every 10% of dropping oil prices would be a 0.1% GDP increase. For this continent, which has been relegated to a second-tier oil producer and energy consumer, private consumption tends to go up, thanks to the cheaper fuels. But because of the strong government presence at the fuel market, and given the relevant excises and other taxes on fuels, the effects of cheaper oil won't be as evident for the end consumer.

In this new situation, the EU which has always been a leading factor in energy innovation and the fight with climate change, will have to find more accessible solutions. Because when oil is so cheap, it's rather difficult to convince the citizens to invest in expensive electric cars, or refurbishing their houses to achieve higher energy efficiency, or pay higher prices for greener energy. Therefore it's logical to expect that quite after the usual European manner, the developers and traders of energy-efficient products would likely ask for subsidies from their governments.

No one would be surprised if the stocks of energy giants like Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron and Exxon Mobil continue to lose their value - in fact, some of them have lost about half of their value in a year. Halting and postponing investments in the sector worth hundreds of billions of dollars has dragged down the companies that supply materials and equipment as well, and also the building companies and steel producers, and the transportation technology companies, etc. It's a chain reaction, including such unpleasant processes like increased financial instability and even a domino-like debt default.

The shareholders and employees in all these industries are hardly that happy with the recent Goldman Sachs and Citigroup forecasts that after Iran (and maybe Libya) return to the global market next year, oil would plunge down to $20 a barrel, at which point commodity markets are very likely to suffer a complete meltdown. They're unlikely to follow the New Year's call to send a thanking card to Saudi king Salman bin Abdulaziz al Saud.

That said, the more industrious among them would probably use the opportunity to find the exact moment when the price of the barrel itself that is used for putting oil in it would exceed that of the oil within it. Then they could start buying lots of barrels of oil, pour the oil out, and start trading with empty barrels. ;)

As for the Peak Oil theorists who used to be very vocal until no so long ago but may've become rather silent lately, I'd tell them not to hasten to despair. They still have a chance of turning out to be right eventually. Or not.

(no subject)

Date: 30/12/15 21:06 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 31/12/15 08:19 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 31/12/15 01:30 (UTC)They're still quite vocal, actually. They aren't being quoted in the mainstream press, of course, since so many have glommed on to the fact that they were likely right.

One thing to note, concerning your observation about growth possibilities outside the US: The US built its infrastructure on really, really cheap gas; Europe did not, opting instead to tax fuels and divert that revenue into social programs. Result? Just as you said, with Germany, et al. probably growing a bit, but with the US still suffering.

Take that fracking "boom". As for fracking, despite all the controversy that surrounds it, it has brought back the theories that thanks to the technological innovations, there's practically no limit to economic development.

Not so fast, Sunshine. Those frackers need oil at $90/barrel just to break even. As many in the "quiet" PO community have noted, crude under $100/barrel kills producers; crude over $100/barrel kills the US economy (again, thanks to our thirsty infrastructure).

Only junk bond funding is carrying these marginal producers; many have folded once the junk bonds stopped flowing. And US banks are carrying a lot of this junk in their portfolios, meaning another cleansing moment is due in our future.

Which is really, really bad news: the banksters managed through the Dodd-Frank Act to close the bailout option; that was well publicized. What was less discussed is the bail in (http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2013/04/economist-explains-2) rescue of a bank, where the depositors get to help a troubled financial institution by giving them every penny therein deposited.

Even worse, those banks have quite likely hedged their fracking junk with derivative contracts, meaning they probably all hold a hedge to the other guys' bad loans. Meaning, just like the housing crisis, when one goes, all have to pay a contract holder shorting the entire industry for their stupidity.

As to PO, go for the long view. The peak started in 2005. We are now in what Hubbert called The Bumpy Plateau, where commodity prices spike and crash with regularity, leading downward supply-wise only in the very long view. We spent 150 years draining this goo; expect the long decline to take another 150 years (provided the short-sighted don't start wars which blow up the reserves before then).

(no subject)

Date: 31/12/15 08:09 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 1/1/16 00:01 (UTC)Actually, when discussing the hydrocarbons predicament, it's useful to review all of M. King Hubbert's predictions, including one few have considered: Exponential Growth as a Transient Phenomenon in Human History (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1M4Ereq_ww74YOKSTFd5iHMoBMM1kPdti2BbYS53X-4KpdObUguaaxKQAEJsG/view?pref=2&pli=1). He reviews (in somewhat overly technical language, but whatever) that our money supply is infinite, but that the stuff from the ground or sky that creates the wealth that should underpin our money is quite finite.

Which means, as we approach an era of discernible limitations to energy, our underpinned economies will start to unravel unless they are re-pinned, something that simply doesn't happen quickly, if at all. Most monetary systems are more likely scrapped than revised, something everyone with a dependence on future wealth should consider.

(no subject)

Date: 3/1/16 00:01 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 3/1/16 07:50 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 31/12/15 15:21 (UTC)