Assessing IP

2/4/12 09:47Once upon a time, I wanted to be a copyright attorney post-graduation. I am enamored of quite a few fields where copyright is a key issue, particularly gaming. Then I took a few IP classes. I still find the law interesting, but for totally different reasons.

Copyright and patent laws are interesting because they are an express command, in the US Constitution, to engage in social engineering. They allow the creation of monopolies to encourage invention and creativity. This has its upsides and downsides, of course. The upside is that owners of the IP get to exploit it for a limited time, and the downside is that only they get to. Since everything is a remix, this sort of restriction is moderately anti-creativity, if we understand that the vast majority of creative people are extremely good at mixing-and-matching things that others have done before. It's presumed that we get more out of it than we lose, though.

But do we? A few examples.

Patents

NASA has a site devoted to telling people how their technology has spun off into things we use every day, a desperate effort to defend their funding. Breast cancer screenings? Thank the guys who sent up a screwy mirror on Hubble. Have a fire in your house? Now it can be put out faster, with less water, thanks to the application of a NASA rocket design. How does this relate to IP, though? Simple: when you work for NASA, you are barred from patenting your discoveries, so they immediately enter the public domain. As a result, Earthly researchers are able to use their techniques for interesting applications without having to first license the patent (if the patent-holder is even willing to license), then hope they make enough off their to pay for that outlay.

Compare that to Technology Enabled Clothing, which is basically a patent on clothes with wire clips for your headphones. The boatload of pockets, for the man-about-town with no inclination to carry a nice messenger bag like a filthy commoner, are conspicuously absent from the patent. This patent has been litigated and defended, and the company is receiving royalty income from other companies who came to this obvious step independently. Instead of innovative cross-use, we have a patent whose sole purpose is to raise the cost of doing business for anyone who comes to an obvious function. They could litigate to fight it, but that's a helluva lot more expensive than just paying the license. Of course, that only works for people with the funds to pay the license, so this isn't exactly entrepreneur-friendly. Though there's been some pushback on some classes of patents, it's debatable how far that goes.

Copyright

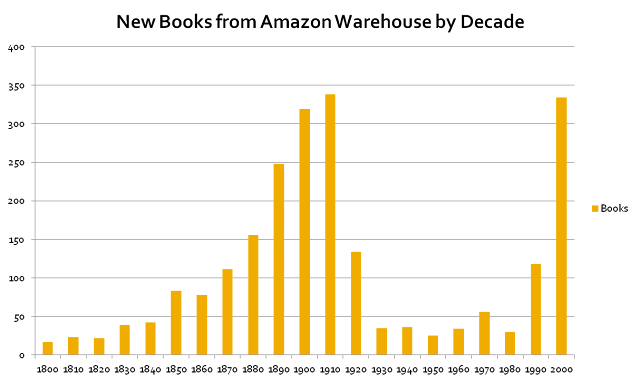

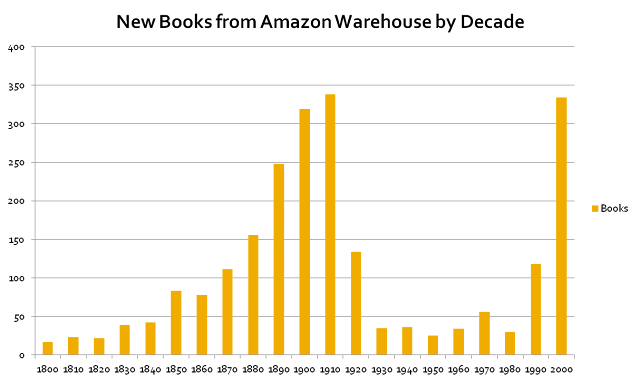

In the realm of copyright, it's actually a lot easier to see the effects of the monopoly. Just ask Amazon.

[Source]

[Source]

Works before 1922 were all in the public domain. Works since 1922 have been repeatedly pulled into longer and longer copyright terms. There's a lot of stuff that has been created since these retroactive extensions were created, all of which was initially created with no expectation that copyright would last longer than 56 years. Since we know why copyright was given, we know that theoretically, a longer copyright means more creations, as more people are incentivized to get into the business of creating.

What encourages creativity?

But we didn't see a huge spike in creativity in the '80s, after the terms were extended. I'd argue that's because we'd hit the limit of what copyright could spur - copyright terms, like everything else, have diminishing returns. Disney and the big content companies argued otherwise*, but when it finally came, the explosion of creativity didn't come from them. It came from lower barriers to creation and publishing. Blogs, iTunes, MySpace (for bands), YouTube, and hundreds of other sites cropped up with the sole goal of making it simple and easy for a content creator to share their stuff with the world, with no cost to them. Moreover, this came in the context of exploding piracy and a general lowering of copyright protections (at least in reality, despite Congress's best efforts).

This suggests something to me: At least in the realm of copyrights, people are more concerned with getting their content out there than with controlling it. Copyrights have a place in reassuring high-cost developers (nobody's gonna publish a $200 million game without some protections) but the terms have long since passed the point where that reassurance was necessary. Instead, they're well into the realm when they stifle creativity by allowing great works to stagnate, incapable of tribute or remixing without a close and careful look at fair use (a realm worthy of its own post).

Patents are a bit more complicated, but I think the NASA examples provide a very good counterfactual to think about. Would we have this super-efficient fire hose or the mammogram screening tech if Hubble had been launched by Space-X, or the rocket engine had been developed by Virgin Galactic? Probably not. They'd be patented for the next twenty years, and just getting the license to play around with the tech would likely be prohibitively expensive. I'm more OK with patents, since their terms are currently reasonable and they generally involve higher costs to develop than copyrightable IP, but I'm wary of overextending them, to things like software and business methods, directions they've been heading for years. These do the exact opposite of what we've seen to encourage creativity: they raise artificial barriers to getting an idea out in the wilderness.

Unless we lower those barriers, we're putting an artificial bottleneck on the innovation that could develop from our increasingly inter-connected, knowledge-based society. We're throttling innovation for the sake of people who don't need the help to keep creating. We're way past promoting progress in Science and the useful Arts.

*Sorry for the cached version, but the main site was down. I'm blaming a Disney DDOS, or DDDOS.

Copyright and patent laws are interesting because they are an express command, in the US Constitution, to engage in social engineering. They allow the creation of monopolies to encourage invention and creativity. This has its upsides and downsides, of course. The upside is that owners of the IP get to exploit it for a limited time, and the downside is that only they get to. Since everything is a remix, this sort of restriction is moderately anti-creativity, if we understand that the vast majority of creative people are extremely good at mixing-and-matching things that others have done before. It's presumed that we get more out of it than we lose, though.

But do we? A few examples.

Patents

NASA has a site devoted to telling people how their technology has spun off into things we use every day, a desperate effort to defend their funding. Breast cancer screenings? Thank the guys who sent up a screwy mirror on Hubble. Have a fire in your house? Now it can be put out faster, with less water, thanks to the application of a NASA rocket design. How does this relate to IP, though? Simple: when you work for NASA, you are barred from patenting your discoveries, so they immediately enter the public domain. As a result, Earthly researchers are able to use their techniques for interesting applications without having to first license the patent (if the patent-holder is even willing to license), then hope they make enough off their to pay for that outlay.

Compare that to Technology Enabled Clothing, which is basically a patent on clothes with wire clips for your headphones. The boatload of pockets, for the man-about-town with no inclination to carry a nice messenger bag like a filthy commoner, are conspicuously absent from the patent. This patent has been litigated and defended, and the company is receiving royalty income from other companies who came to this obvious step independently. Instead of innovative cross-use, we have a patent whose sole purpose is to raise the cost of doing business for anyone who comes to an obvious function. They could litigate to fight it, but that's a helluva lot more expensive than just paying the license. Of course, that only works for people with the funds to pay the license, so this isn't exactly entrepreneur-friendly. Though there's been some pushback on some classes of patents, it's debatable how far that goes.

Copyright

In the realm of copyright, it's actually a lot easier to see the effects of the monopoly. Just ask Amazon.

[Source]

[Source]Works before 1922 were all in the public domain. Works since 1922 have been repeatedly pulled into longer and longer copyright terms. There's a lot of stuff that has been created since these retroactive extensions were created, all of which was initially created with no expectation that copyright would last longer than 56 years. Since we know why copyright was given, we know that theoretically, a longer copyright means more creations, as more people are incentivized to get into the business of creating.

What encourages creativity?

But we didn't see a huge spike in creativity in the '80s, after the terms were extended. I'd argue that's because we'd hit the limit of what copyright could spur - copyright terms, like everything else, have diminishing returns. Disney and the big content companies argued otherwise*, but when it finally came, the explosion of creativity didn't come from them. It came from lower barriers to creation and publishing. Blogs, iTunes, MySpace (for bands), YouTube, and hundreds of other sites cropped up with the sole goal of making it simple and easy for a content creator to share their stuff with the world, with no cost to them. Moreover, this came in the context of exploding piracy and a general lowering of copyright protections (at least in reality, despite Congress's best efforts).

This suggests something to me: At least in the realm of copyrights, people are more concerned with getting their content out there than with controlling it. Copyrights have a place in reassuring high-cost developers (nobody's gonna publish a $200 million game without some protections) but the terms have long since passed the point where that reassurance was necessary. Instead, they're well into the realm when they stifle creativity by allowing great works to stagnate, incapable of tribute or remixing without a close and careful look at fair use (a realm worthy of its own post).

Patents are a bit more complicated, but I think the NASA examples provide a very good counterfactual to think about. Would we have this super-efficient fire hose or the mammogram screening tech if Hubble had been launched by Space-X, or the rocket engine had been developed by Virgin Galactic? Probably not. They'd be patented for the next twenty years, and just getting the license to play around with the tech would likely be prohibitively expensive. I'm more OK with patents, since their terms are currently reasonable and they generally involve higher costs to develop than copyrightable IP, but I'm wary of overextending them, to things like software and business methods, directions they've been heading for years. These do the exact opposite of what we've seen to encourage creativity: they raise artificial barriers to getting an idea out in the wilderness.

Unless we lower those barriers, we're putting an artificial bottleneck on the innovation that could develop from our increasingly inter-connected, knowledge-based society. We're throttling innovation for the sake of people who don't need the help to keep creating. We're way past promoting progress in Science and the useful Arts.

*Sorry for the cached version, but the main site was down. I'm blaming a Disney DDOS, or DDDOS.

(no subject)

Date: 3/4/12 21:24 (UTC)Patents are more complicated, and generally more case-by-case, in terms of the necessity. I presume that the law simply can't reach the level of complexity that would require, though. For something that's not easily reverse-engineered (like, say, biotech processes like cloning or DNA isolation) then patents may not be necessary, as the individual creating the process can exercise sufficient control on their own to want to bring it to market. For something that's costly to develop, but easily reverse-engineered, patents are more likely necessary to encourage the creator to bring the product to market. Here I'm thinking of new processes for, say, curing rubber or cooling a blast furnace's exterior, stuff that once you see how it works, you can easily create your own rip off. Why would you spend all the time experimenting with different temps and exposure times to make better rubber if the next guy could just waltz in and take it?

Obviously costs and benefits are difficult to calculate. Do you measure by the value of the song commercially, or by its artistic merit (which is presumably what you actually want to create)? Do you measure the invention by how far it moves the field forward, or how much it cost to develop, or how difficult it would be to replicate absent instructions from the inventor?