Assessing IP

2/4/12 09:47Once upon a time, I wanted to be a copyright attorney post-graduation. I am enamored of quite a few fields where copyright is a key issue, particularly gaming. Then I took a few IP classes. I still find the law interesting, but for totally different reasons.

Copyright and patent laws are interesting because they are an express command, in the US Constitution, to engage in social engineering. They allow the creation of monopolies to encourage invention and creativity. This has its upsides and downsides, of course. The upside is that owners of the IP get to exploit it for a limited time, and the downside is that only they get to. Since everything is a remix, this sort of restriction is moderately anti-creativity, if we understand that the vast majority of creative people are extremely good at mixing-and-matching things that others have done before. It's presumed that we get more out of it than we lose, though.

But do we? A few examples.

Patents

NASA has a site devoted to telling people how their technology has spun off into things we use every day, a desperate effort to defend their funding. Breast cancer screenings? Thank the guys who sent up a screwy mirror on Hubble. Have a fire in your house? Now it can be put out faster, with less water, thanks to the application of a NASA rocket design. How does this relate to IP, though? Simple: when you work for NASA, you are barred from patenting your discoveries, so they immediately enter the public domain. As a result, Earthly researchers are able to use their techniques for interesting applications without having to first license the patent (if the patent-holder is even willing to license), then hope they make enough off their to pay for that outlay.

Compare that to Technology Enabled Clothing, which is basically a patent on clothes with wire clips for your headphones. The boatload of pockets, for the man-about-town with no inclination to carry a nice messenger bag like a filthy commoner, are conspicuously absent from the patent. This patent has been litigated and defended, and the company is receiving royalty income from other companies who came to this obvious step independently. Instead of innovative cross-use, we have a patent whose sole purpose is to raise the cost of doing business for anyone who comes to an obvious function. They could litigate to fight it, but that's a helluva lot more expensive than just paying the license. Of course, that only works for people with the funds to pay the license, so this isn't exactly entrepreneur-friendly. Though there's been some pushback on some classes of patents, it's debatable how far that goes.

Copyright

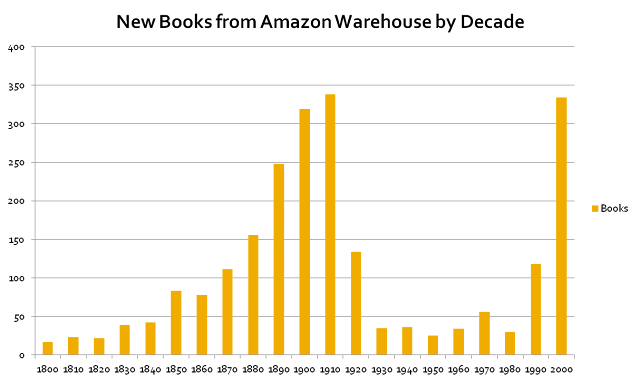

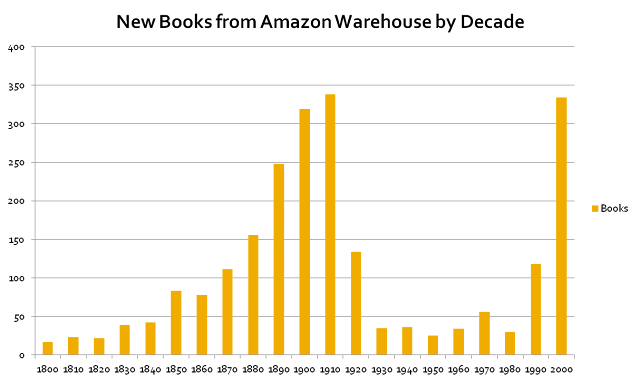

In the realm of copyright, it's actually a lot easier to see the effects of the monopoly. Just ask Amazon.

[Source]

[Source]

Works before 1922 were all in the public domain. Works since 1922 have been repeatedly pulled into longer and longer copyright terms. There's a lot of stuff that has been created since these retroactive extensions were created, all of which was initially created with no expectation that copyright would last longer than 56 years. Since we know why copyright was given, we know that theoretically, a longer copyright means more creations, as more people are incentivized to get into the business of creating.

What encourages creativity?

But we didn't see a huge spike in creativity in the '80s, after the terms were extended. I'd argue that's because we'd hit the limit of what copyright could spur - copyright terms, like everything else, have diminishing returns. Disney and the big content companies argued otherwise*, but when it finally came, the explosion of creativity didn't come from them. It came from lower barriers to creation and publishing. Blogs, iTunes, MySpace (for bands), YouTube, and hundreds of other sites cropped up with the sole goal of making it simple and easy for a content creator to share their stuff with the world, with no cost to them. Moreover, this came in the context of exploding piracy and a general lowering of copyright protections (at least in reality, despite Congress's best efforts).

This suggests something to me: At least in the realm of copyrights, people are more concerned with getting their content out there than with controlling it. Copyrights have a place in reassuring high-cost developers (nobody's gonna publish a $200 million game without some protections) but the terms have long since passed the point where that reassurance was necessary. Instead, they're well into the realm when they stifle creativity by allowing great works to stagnate, incapable of tribute or remixing without a close and careful look at fair use (a realm worthy of its own post).

Patents are a bit more complicated, but I think the NASA examples provide a very good counterfactual to think about. Would we have this super-efficient fire hose or the mammogram screening tech if Hubble had been launched by Space-X, or the rocket engine had been developed by Virgin Galactic? Probably not. They'd be patented for the next twenty years, and just getting the license to play around with the tech would likely be prohibitively expensive. I'm more OK with patents, since their terms are currently reasonable and they generally involve higher costs to develop than copyrightable IP, but I'm wary of overextending them, to things like software and business methods, directions they've been heading for years. These do the exact opposite of what we've seen to encourage creativity: they raise artificial barriers to getting an idea out in the wilderness.

Unless we lower those barriers, we're putting an artificial bottleneck on the innovation that could develop from our increasingly inter-connected, knowledge-based society. We're throttling innovation for the sake of people who don't need the help to keep creating. We're way past promoting progress in Science and the useful Arts.

*Sorry for the cached version, but the main site was down. I'm blaming a Disney DDOS, or DDDOS.

Copyright and patent laws are interesting because they are an express command, in the US Constitution, to engage in social engineering. They allow the creation of monopolies to encourage invention and creativity. This has its upsides and downsides, of course. The upside is that owners of the IP get to exploit it for a limited time, and the downside is that only they get to. Since everything is a remix, this sort of restriction is moderately anti-creativity, if we understand that the vast majority of creative people are extremely good at mixing-and-matching things that others have done before. It's presumed that we get more out of it than we lose, though.

But do we? A few examples.

Patents

NASA has a site devoted to telling people how their technology has spun off into things we use every day, a desperate effort to defend their funding. Breast cancer screenings? Thank the guys who sent up a screwy mirror on Hubble. Have a fire in your house? Now it can be put out faster, with less water, thanks to the application of a NASA rocket design. How does this relate to IP, though? Simple: when you work for NASA, you are barred from patenting your discoveries, so they immediately enter the public domain. As a result, Earthly researchers are able to use their techniques for interesting applications without having to first license the patent (if the patent-holder is even willing to license), then hope they make enough off their to pay for that outlay.

Compare that to Technology Enabled Clothing, which is basically a patent on clothes with wire clips for your headphones. The boatload of pockets, for the man-about-town with no inclination to carry a nice messenger bag like a filthy commoner, are conspicuously absent from the patent. This patent has been litigated and defended, and the company is receiving royalty income from other companies who came to this obvious step independently. Instead of innovative cross-use, we have a patent whose sole purpose is to raise the cost of doing business for anyone who comes to an obvious function. They could litigate to fight it, but that's a helluva lot more expensive than just paying the license. Of course, that only works for people with the funds to pay the license, so this isn't exactly entrepreneur-friendly. Though there's been some pushback on some classes of patents, it's debatable how far that goes.

Copyright

In the realm of copyright, it's actually a lot easier to see the effects of the monopoly. Just ask Amazon.

[Source]

[Source]Works before 1922 were all in the public domain. Works since 1922 have been repeatedly pulled into longer and longer copyright terms. There's a lot of stuff that has been created since these retroactive extensions were created, all of which was initially created with no expectation that copyright would last longer than 56 years. Since we know why copyright was given, we know that theoretically, a longer copyright means more creations, as more people are incentivized to get into the business of creating.

What encourages creativity?

But we didn't see a huge spike in creativity in the '80s, after the terms were extended. I'd argue that's because we'd hit the limit of what copyright could spur - copyright terms, like everything else, have diminishing returns. Disney and the big content companies argued otherwise*, but when it finally came, the explosion of creativity didn't come from them. It came from lower barriers to creation and publishing. Blogs, iTunes, MySpace (for bands), YouTube, and hundreds of other sites cropped up with the sole goal of making it simple and easy for a content creator to share their stuff with the world, with no cost to them. Moreover, this came in the context of exploding piracy and a general lowering of copyright protections (at least in reality, despite Congress's best efforts).

This suggests something to me: At least in the realm of copyrights, people are more concerned with getting their content out there than with controlling it. Copyrights have a place in reassuring high-cost developers (nobody's gonna publish a $200 million game without some protections) but the terms have long since passed the point where that reassurance was necessary. Instead, they're well into the realm when they stifle creativity by allowing great works to stagnate, incapable of tribute or remixing without a close and careful look at fair use (a realm worthy of its own post).

Patents are a bit more complicated, but I think the NASA examples provide a very good counterfactual to think about. Would we have this super-efficient fire hose or the mammogram screening tech if Hubble had been launched by Space-X, or the rocket engine had been developed by Virgin Galactic? Probably not. They'd be patented for the next twenty years, and just getting the license to play around with the tech would likely be prohibitively expensive. I'm more OK with patents, since their terms are currently reasonable and they generally involve higher costs to develop than copyrightable IP, but I'm wary of overextending them, to things like software and business methods, directions they've been heading for years. These do the exact opposite of what we've seen to encourage creativity: they raise artificial barriers to getting an idea out in the wilderness.

Unless we lower those barriers, we're putting an artificial bottleneck on the innovation that could develop from our increasingly inter-connected, knowledge-based society. We're throttling innovation for the sake of people who don't need the help to keep creating. We're way past promoting progress in Science and the useful Arts.

*Sorry for the cached version, but the main site was down. I'm blaming a Disney DDOS, or DDDOS.

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 15:07 (UTC)Somewhat ironically, why did we get to the moon so quickly? Why did we get so many benefits? More to the point, why do we have no actual plans to go back to the moon now, never mind Mars and beyond? Competition. The space race created significant competition for this sort of endeavor between us and the Soviets, something that isn't happening between governments anymore in this era of cooperation. Meanwhile, all the rocketry advances are happening via the private sector with the different X programs.

I think you're making some interesting observations, but making some incorrect conclusions. While many of the technologies that you're talking about may not have been public domain, that doesn't necessarily mean that the technologies we're talking about would not have been licensed and put forward in other ways. After all, the existence of copyright on plenty of technology endeavors on the internet and in computing has not halted innovation in any meaningful way - Apple and Google in particular are vicious regarding copyright and are among the most innovative groups out there, and the open source movement continues to compete in other areas as well.

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 15:19 (UTC)But Hubble image-processing techniques and the rocket engine designed were post-Space Race. I'll admit that the precursors may not have been there without the Race, but it's important to note that the tech from the Space Race wasn't patented, either. Competition might've driven that, but patents didn't. It's fallacious to presume that patents and competition are interchangeable.

After all, the existence of copyright on plenty of technology endeavors on the internet and in computing has not halted innovation in any meaningful way

Well, that's hard to say. Copyright is interesting because it distorts the market by design, causing innovation to flow around these islands of stable IP that have already been claimed by other companies. You've also got the question backwards, which I find surprising given your small-government proclivities. It's not whether the IP monopoly has decreased innovation, but whether the content of the current IP monopoly was necessary to encourage the innovation we got. I figured you'd be on board with a least-restrictive-means sort of IP regulation.

Apple and Google in particular are vicious regarding copyright

You mean patents. Google in particular has pushed many boundaries backwards on copyright, including trying (unsuccessfully (http://technologizer.com/2011/03/23/unsettled-judge-says-google-book-deal-would-be-monopoly/)) to get a presumptive license for Google Books. As for their defense of patents: what good has that done us? Many things that the iPhone uses, like the touchscreen display and putting app icons on a grid, are patented, and the source of intense litigation for what are basically requirements for a halfway-orderly user experience. Should that really be patented? I don't think so. It's meant that only the "big dogs" can get into the smartphone game, because they have the money to fight it out. ETA: Moreover, these are things that made it into every competitor's product regardless of Apple's patents - and Apple is still trouncing all of them quite handily. So was the patent necessary for that innovation? We should also remember that Google and Apple are themselves victims of the current patent structure, facing frequent lawsuits from "patent trolls" (http://www.tomshardware.com/news/patent-infringement-lawsuit-apple-dell,15103.html) and spending billions to build defensive patent portfolios for products they've already developed (http://news.cnet.com/8301-30686_3-20092399-266/google-just-bought-itself-patent-protection/).

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 15:28 (UTC)I'm not trying to say they're interchangeable, but I am saying that the race made those things possible. The competition is what drove those technologies, not the openness of government works.

To put it another way, are you arguing that, say, we wouldn't have as much image processing ability had the Hubble processes been patented? I'm not sure that's true.

It's not whether the IP monopoly has decreased innovation, but whether the content of the current IP monopoly was necessary to encourage the innovation we got. I figured you'd be on board with a least-restrictive-means sort of IP regulation.

I'm actually on board with heavily-restrictive IP regulation with very bright lines as to usage - bright lines that don't really exist currently. I don't want to derail this with my longer-form ideas regarding how we do copyright and patents, however.

You mean patents.

I'm using the terms interchangeably here when I shouldn't be, I know.

As for their defense of patents: what good has that done us? Many things that the iPhone uses, like the touchscreen display and putting app icons on a grid, are patented, and the source of intense litigation for what are basically requirements for a halfway-orderly user experience. Should that really be patented? I don't think so.

I disagree. The question, to me, is whether the touch-screen advances would have existed if they couldn't patent them. I'm not convinced that would be the case. You also at least appear to be saying that the litigation is a bad thing, and I'm not convinced of that, either. I'm not sure why the court of law is nt a good place to hash that kind of thing out.

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 15:52 (UTC)I'm actually for pretty hefty patent protections, but I think they should be limited in term (where, thankfully, Congress agrees with me) and limited in scope (where the courts and Congress do not seem to agree with me). Copyrights, IMO, have mostly just vastly overreached the usefulness of extending the terms, though they're about right in terms of the protections that exist. Keeping the two separate is somewhat important to the overall argument.

You also at least appear to be saying that the litigation is a bad thing, and I'm not convinced of that, either. I'm not sure why the court of law is nt a good place to hash that kind of thing out.

Litigation is an artificial expense, a barrier to entry. It's only a good thing to determine who has the rights if we need to have sole possession of rights. So, I think you're begging the overall question.

Also, I meant to restrict my "should that really be patented" question to things like the icon grid (http://arstechnica.com/apple/news/2011/04/bad-touchwiz-apple-sues-samsung-for-patent-violations.ars), something that's existed in the Windows since at least Windows ME (I can't recall whether Win95 had the grid icon version), released in 2000. Touchscreens, to me, fall clearly under patentable tech, whereas the icon grid patent gets away with it because patent examiners are too overworked to actually check the prior art for either novelty or non-obviousness in any rigorous way. Part of that would be restoring lost resources (http://www.generalpatent.com/patent-office-fy2011-budget-slashed-100-million) to the USPTO, and making them an actual enforcement and examination body rather than a slow-moving rubber stamp. That's doubly true if we're going to give judicial deference (http://stlr.stanford.edu/pdf/BuchananJ-Deference.pdf) to PTO decisions.

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 16:18 (UTC)To put it another way, are you arguing that, say, we wouldn't have as much image processing ability had the Hubble processes been patented? I'm not sure that's true.

I think it's a lot less certain. I don't know that you can say that the Hubble processes, in particular, weren't driven by the openness of government works. I mean, we can trace these things back infinitely - the space race never would've happened if Hitler didn't need rockets to hit England with, and that never would've happened if... and on and on. I'm saying that this particular tech, the image processing used in breast cancer screening, was uniquely enabled by the lack of patent protection. It might've come about anyway (although likely later, at a higher cost overall due to the need to license or litigate), but the patents add that "might," that element of uncertainty. They're supposed to dispel that. This could be a problem.

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:13 (UTC)I may be naive on the issue of patent trolls. I'm way behind on my TAL, so I haven't heard that show yet, but I've so far viewed it more of the shakeout of a fast-moving technological age than much else. I could be way, way off.

But then ask yourself what IP does - does it enable or hinder competition?

I'd argue enable. Why? It forces people to come up with novel ideas of achievement than all working off of the same script. It may result in the same or similar conclusions, but the more spitballing that occurs, the better chances for positive results.

All things being equal - let's say a widget is produced in two alternative timelines, one with IP protection and one without. Which one do you think has a market with a greater degree of competition for that widget, widgets like it, improvements on the widget, etc?

Hard to say in my mind. What if that widget is Windows versus Linux, for example? Common sense tells me the more open platform is going to have the better market in this scenario, but I'm not convinced history is necessarily following.

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 22:15 (UTC)In the case of Copyright, there is something else at stake. As an artist myself, I do see value in it in that what I make artistically, is actually a reflection of my own ideas and statements. If I draw a character to represent my own ideas, and another is created closely enough to mine that my voice is now co-opted by the voice of the copier (such that it is assumed that I drew both), then it gets somewhat too close to forgery in my mind.

That said, the current state of affairs with Copyright has gotten ridiculous as well, such that what is being sought to be copyrighted is less and less about the specific expressions.

(no subject)

Date: 5/4/12 02:59 (UTC)I think public disclosure is one of the fundamental principles underlying the patent system that is missing in this discussion. We create limited monopolies by granting the right to restrict the use and sale of a particular invention not just because we want to promote innovation and individuals and/or companies won't create things without the incentive of a monopoly (an assumption that I have a difficult time believing), but because we want people to publicly disclose their creations so that others can figure out how something was made and make it better, faster, stronger, etc. People and companies have always made things without the incentive of a monopoly. Full stop. They usually protect those inventions by limiting disclosure of how they did it. The patent system is used to incentivize disclosure by granting a limited monopoly over the claimed invention. Its why claim construction and Markman is so important. You only get a monopoly over what you disclosed. Full-stop.

Which brings me to the "diminishing returns". Plenty of people say that we need patents, just for brief periods. This implies a calculation is being made - the cost of the patent is worth the benefit of what it provides. While I grant a sense of reasonableness to these arguments, I haven't seen anyone attempt to provide this calculation.

I don't think its possible to actually provide such a calculation. How do you measure the benefit of disclosure of any patent without the benefit of hindsight? Some patents will be more beneficial than others. How can you predict that without the benefit of hindsight? Who gets to decide if its beneficial or not? Congress? A jury? The Courts? The PTO? Individual patent examiners?

I think the patent term (which is currently 20 years, with a 6 year 'look-back' for damages once you file a complaint for infringement) is society's attempt to (1) reasonably balance the cost of the patent versus the benefit it provides to society by disclosure of the invention and (2) provide an efficient and predictable system that companies and individuals can rely on to make decisions.

Do I think society got it wrong? Is the twenty year term too generous? In my opinion, yes, particularly in the tech industry. Twenty years ago, we didn't even have cell phones. Now we have cell phones that would put a twenty-year-old computer to shame. Would it be possible to conduct studies across industries in order to determine the "most reasonable" patent term for each industry in light of the fact that the purpose of the patent system is to facilitate innovation through disclosure? Sure. But, IMO, any such calculation would necessarily involve variables and assumptions that would make finding the "one true calculation" exceedingly difficult.

At any rate, thanks for the fascinating discussion. Your steam engine link at mises didn't work earlier, but I'm going to try it again later. It sounds very interesting.

Also if you're interested in keeping up with patent law (generally), the blog Patently-O is pretty darn good at keeping track of current events (be they legislative, administrative, or judicial).

(no subject)

Date: 3/4/12 20:41 (UTC)It dramatically changes competition from using Trade Secrets usage and industrial espionage to open-world competition.

Moreover - number of patents is rising dramatically over years, as well as money paid for them.

That acceleration is only possible because of protection of IP.

Do you count robbery as a competition?

Why stealing other's idea and improvements is considered as competitive?

Imagine two creators spent their life for invention:

one is protected by law, another isn't.

Which one will survive and can get access to the credit resources better than other?

If you grew potato you aren't expecting competition from those who stole it.

However from "potato" consumer standpoint of view, it is nice to allow the thief to sell potato and "compete" with you!

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 15:53 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 16:01 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 16:29 (UTC)BTW, when I read that you had taken IP classes, I first got the impression that you were interested in machine connectivity protocols.

A few years back, I learned that the open source community was a major service provider to Microsoft. They had a choice: either they help Mr. Monopole to fix his connectivity bugs or lose connectivity altogether. They chose the former course. It also got them access to Mickey sources.

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:02 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:04 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:25 (UTC)I always love this interview with Harlan Ellison about "Pay the writer." In my case, I modify it a bit to "pay the music editor!" ;)

(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:26 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:33 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:54 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 18:54 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 2/4/12 19:37 (UTC)Our tradition of recognizing IP is dangerous though in that it results in the deification of the publicly recognized "thinker", "inventor" and "artist" at the expense of everyone else. When ideas are always associated with proper names (and always the same proper names, in point of fact), this suggests that thinking and creating are special skills that belong to a select few individuals.

Another incidental drawback of our association of ideas with specific individuals is that it promotes the acceptance of these ideas in their original form. The students who learn a philosophical system are encouraged to learn it in its orthodox form, rather than learning the parts which they find relevant to their own lives and interests and combining these parts with ideas from other sources. Out of deference to the original thinker, deified as they are in our tradition, their texts and theories are to be preserved as-is, without ever being put into new forms or contexts which might reveal new insights. Mummified as they are, many theories become completely irrelevant to modern existence, when they could have been given a new lease on life by being treated with a little less reverence.

After all, a good idea should be available to everyone—should belong to everyone—if it really is a good idea. In a society organized with human happiness as the objective, copyright infringement laws and similar restrictions only hinder the free distribution and recombination of ideas. These impediments only make it more difficult for individuals who are looking for challenging and inspiring material to come upon it and share it with others.

Remember the Free Software and then Open Source movements?

(no subject)

Date: 3/4/12 03:32 (UTC)For me, the commentary to highlight there was this bit:

It is clear that the Court zeroed in on their core concern – of tipping the balance from the exclusivity of a patent grant on one hand and the flow of information needed for future innovation on the other. Whenever the Court mentions a “balance,” the patent bar should get nervous because invariably, “balancing tests” will soon find their way into future lower court decisions that bear little semblance to what (we think) the Court intended in the decision.

(no subject)

Date: 3/4/12 11:46 (UTC)(no subject)

Date: 3/4/12 20:26 (UTC)1. Patent doesn't mean NOBODY can use it. In fact they mean right opposite to it: patent mean everybody can use it for the fee or royalty.

Patent-holder actually happy if somebody uses it and pays for it.

It's a lie that prices higher than it should be.

It's a lie that you can't do incremental invention, based on other patents, you can and honestly lawyer must know that you can gain benefits regarding rights to use parental patent when you got sub-patent based on it.

2. As a Marxist you think about gain from the intellectual property, from the perspective of it's cost to create.

This is wrong. You should look at it from the perspective of how important it is.

And based on price voluntarily paid for patents - it is very important.

3. Even if you are a Marxist, when you consider IP cost, take into account that this cost multiplied by the factor of failed projects needed to get this one success.

(no subject)

Date: 3/4/12 20:39 (UTC)It's a lie that you can't do incremental invention, based on other patents, you can and honestly lawyer must know that you can gain benefits regarding rights to use parental patent when you got sub-patent based on it.

Not true, in the US. Here, you can gain a patent "downstream" of existing patents (so, I could get a patent for a refinement of iPhone touchscreen tech) but you cannot exploit that patent until the original patent, off of which you are "piggybacking," has expired. Even then, experimenting with the patented technology may be barred, if the holder seeks to enforce it, so you'd have trouble reducing to practice outside of the patent application, which is a lot of money to go through if you can't even build a prototype.

2. I'm not a Marxist, and I don't look at IP from a cost-to-produce standpoint. I look at patents and other IP from the perspective of asking what protections are necessary to incentivize creativity. Period. If it's very cheap to develop but single-use, arguably you need greater protections than someone with a hard-to-replicate process which would act as its own functional bar to the reproduction of the invention. The question I'm trying to ask is if we have protections so extensive that they've passed the point of maximum return, recognizing that each protection comes with a corresponding cost to cross-use and other innovation in the same field.

3. Irrelevant, see #2.

(no subject)

Date: 3/4/12 21:24 (UTC)Patents are more complicated, and generally more case-by-case, in terms of the necessity. I presume that the law simply can't reach the level of complexity that would require, though. For something that's not easily reverse-engineered (like, say, biotech processes like cloning or DNA isolation) then patents may not be necessary, as the individual creating the process can exercise sufficient control on their own to want to bring it to market. For something that's costly to develop, but easily reverse-engineered, patents are more likely necessary to encourage the creator to bring the product to market. Here I'm thinking of new processes for, say, curing rubber or cooling a blast furnace's exterior, stuff that once you see how it works, you can easily create your own rip off. Why would you spend all the time experimenting with different temps and exposure times to make better rubber if the next guy could just waltz in and take it?

Obviously costs and benefits are difficult to calculate. Do you measure by the value of the song commercially, or by its artistic merit (which is presumably what you actually want to create)? Do you measure the invention by how far it moves the field forward, or how much it cost to develop, or how difficult it would be to replicate absent instructions from the inventor?